Are Yiddish and German the same language? What are the differences between them?” The answer to that is “No!”. They are different languages. They are often confused with each other because the Yiddish sound pretty much like German.

Can Yiddish speakers understand german?

Basically, Yiddish speakers could understand the context of a German conversation.

Can german speakers understand Yiddish?

From my experience, German native speaker could hardly understand Yiddis, mostly because during the years, the Yiddish language gathered words and phrases from several other languages. That is why it would make it more difficult for German speakers to understand Yiddish,

What is the difference between biblical Hebrew and Modern Hebrew?

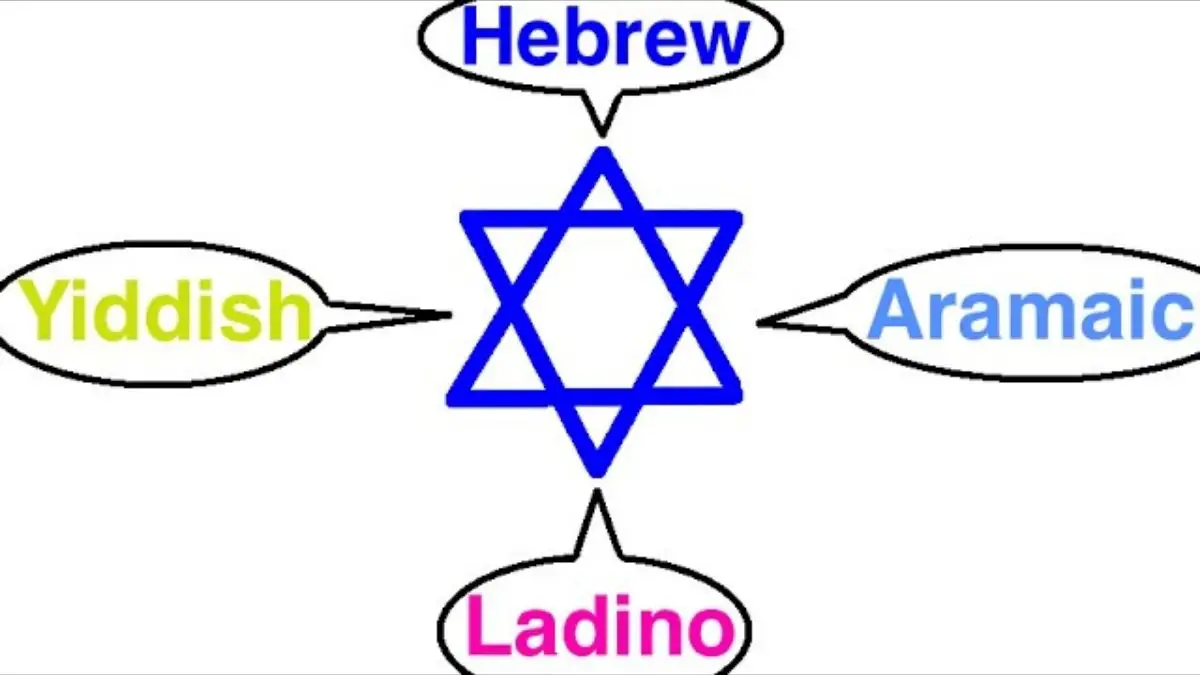

The Hebrew language, used for worship and religious study by Jews all over the world—in places as distant as Yemen, Greece, and Poland—helped the Jewish people to retain their sense of commonality Moreover, Jewish communities in various countries developed their own dialects, such as Yiddish, to use in everyday life.

For thousands of years and without interruption, Hebrew has been the universal language of Judaism used for prayer and worship. Hebrew is one of the world’s oldest languages, dating perhaps as far back as 4,000 B.C.E. The early Hebrews conversed in Hebrew, a Semitic idiom of the Canaanite group that includes Arabic. The patriarchs spoke Hebrew as they made their way into the Promised Land, and it remained the language of the Hebrews throughout the biblical period.

However, in the fifth century B.C.E., when Jews began to return to Israel from Babylon, where many had lived after the destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C.E., most of the inhabitants of Palestine conversed in Aramaic, which gradually infiltrated the Hebrews’ language. A few centuries later, Hebrew had all but ceased to exist as a spoken language. It would not be reestablished as such for two millennia.

Today, many observant Jews take on the task of studying Hebrew. Hebrew is not the easiest language to learn. For starters, it is read from right to left, just the opposite of reading English. Those who study Hebrew also have to learn a new alphabet with twenty-two consonants, five of which assume a different form when they appear at the end of a word. And if this isn’t enough of a challenge, Hebrew is generally written without vowel sounds!

Actually, the absence of vowels is common in Semitic languages. The convention dates back to Hebrew’s earliest days, when most people were fluent in the language and had no need for vowels in order to read it. However, literacy declined, especially after the destruction of the Second Temple when the Jews commenced their 2,000-year-long Diaspora. Sometime around the eighth century C.E., rabbis came up with an answer to help increase the number of Jews who could become literate in Hebrew—the nikkudim (points), a system of dots, dashes, and lines that are situated just about anywhere (above, below, beside, or inside the consonants). Most nikkudim indicate vowels; when nikkudim appear in the text, it is called pointed text and is obviously easier to read.

While nikkudim appear in prayer books and in many texts, especially books for children, only the consonants are used in Torah scrolls or the parchment inside tefillin (leather boxes that contain scrolls with scripture passages, bound to the arm and forehead during Jews’ morning prayer) and mezuzot (scrolls of parchment affixed to the doorpost).

The entire style of writing Hebrew in the sacred scrolls is different. In contrast to the block print that is customarily seen in Hebrew books, sacred documents are written in a style that utilizes “crowns” on many of the letters. These crowns resemble crows’ feet that emanate from the upper points. This type of writing is known as “STA’M” (an abbreviation for Sifrei, Torah, Tefillin, and Mezuzot).

A more modern cursive form of writing is frequently employed for handwriting. Yet another style, Rashi script, appears in certain texts to differentiate the body of the text from the commentary This kind of text, named in honor of Rashi, the great commentator on the Torah and Talmud, is used for the exposition.

Further, the Hebrew numerical system uses letters as digits in the same way that Roman numerals are letters of the Latin alphabet. In Hebrew, though, each letter of the alphabet has a corresponding numerical value. The first ten letters have values of one through ten; the next nine have values of twenty through 100, counting by tens; and the remaining letters have values of 200, 300, and 400, respectively.

Unlike the Roman numerical system where the order of the letters is important, in the Hebrew system the sequence of the letters is irrelevant. The letters are simply added to determine the total value.

Since every Hebrew word can be calculated to represent a number, Jewish mysticism has been painstakingly engaged in discerning the hidden meanings in words’ numerical value. For example, the numerical value of the Hebrew word chai (life) is eighteen. Hence, it is a common practice to make charitable contributions and give gifts, especially for weddings and bar or bat mitzvahs, in multiples of eighteen.

Hebrew language revival history

Travel through modern Israel, and you will see the Hebrew letters that Diaspora Jews associate with prayer books filling the pages of newspapers and magazines, blaring messages on billboards, posted on cereal boxes, and plastered all over for-rent signs. Some visitors find this nothing short of miraculous.

For most of the second millennium, Hebrew was rarely spoken other than during religious observances or by scholars studying Torah and other sacred tomes. However, in the nineteenth century, Hebrew underwent a renaissance. Thanks in large part to Eliezer ben Yehudah, a Lithuanian Jewish scholar and leader who dedicated himself to the revival of Hebrew and introduced thousands of modern terms to the ancient language, Hebrew regained its status as a vernacular language.

Reinforcing Hebrew’s rescue from near extinction as a spoken tongue, the twentieth-century Zionist movement decided that Hebrew should become the language of the modern State of Israel once the Jewish homeland was established. As a result, Hebrew was recognized as the official language of Jewish Palestine in 1922.

Naturally, additional adjustments had to be made to Eliezer ben Yehudah’s earlier efforts to bring Hebrew up to date. After all, the language had lain dormant for thousands of years. Much was new in the way of technology and devices, and the world was a different place. Consequently, the Hebrew of worship and religious scholarship is not exactly the same as modern Hebrew accepted as the new State of Israel’s official language in 1948.

There is a difference between the Sephardic and Ashkenazi way of pronouncing several Hebrew vowels and one consonant. Because Israel has adopted Sephardic pronunciation for modern Hebrew, most Ashkenazim are adopting the Sephardic method of pronunciation.

Today, more than four and a half million people speak modern Hebrew. While Hebrew is the principal language for Israeli Jews, it is also a second language for many Israeli Arabs and recent immigrants. And, of course, Jews living outside of Israel may also be fluent in modern Hebrew.

Hebrew writing alphabet

In the early part of the twentieth century, as a result of wars, revolutions, and persecutions, many Yiddish writers fled Eastern Europe for the United States. Consequently, New York became a Yiddish literary center almost equal to Warsaw in stature. Notable during this time were Abraham Reisen, who wrote poetry and short stories, and Sholem Asch, who, along with Israel Joshua Singer, helped perfect the Yiddish novel. Israel Singer’s younger brother, Isaac Bashevis Singer, emerged as one of the most well-known Yiddish writers of short stories and novels.

In the Soviet Union, Yiddish writers pursued themes of social realism. Among these writers, many of whom were murdered in the purge of Yiddish writers and poets during the Stalin era, were the poet Moshe Kulbak, the novelist David Bergelson, and short-story writer Isaak Babel.

Today, Yiddish is in decline, and despite renewed interest in Yiddish literature, little new work is forthcoming. However, Jewish literature that isn’t written in Yiddish, both religious and secular, abounds. So much so, in fact, it could easily fill voluminous anthologies.

Wherever Jews live in respectable numbers, there is a presence of Jewish literature that augments their sense of oneness as a people. In the last fifty years, American Jewish literature has flourished—if, that is, you count all types of work written by Jewish writers as Jewish literature.

A variety of well-established Jewish American writers have achieved critical acclaim, including Saul Bellow, Henry Roth, Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, Joseph Heller, Elie Wiesel, Chaim Potok, Cynthia Ozick, and Leon Uris. With young writers of fiction such as Michael Chabon, Myla Goldberg, Thane Rosenbaum, and Allegra Goodman, the future of Jewish literature in twenty-first century America is secure.

Not only have Israeli novelists had a great impact on Israelis, their work has been translated from Hebrew, making them accessible to Jewish communities around the globe. We have been fortunate to witness the likes of Aharon Appelfeld, S. Y. Agnon, A. B. Yehoshua, and Amos Oz, as well as the emergence of a new generation of gifted Israeli writers such as David Grossman and Etgar Keret.

Yiddish origin

Traditionally through the ages, Jewish women were not taught Hebrew, and so they spoke Yiddish, a vernacular that is a mix of Middle High German, with a measure of Hebrew, and touches of Slavic tongues and Loez (a combination of Old French and Old Italian). Naturally, Jewish women spoke Yiddish to their children, who, in turn, spoke it to their own children. Thus, Yiddish became known as mame loshen, the “mother’s language,” as opposed to Hebrew, loshen ha-kodesh, or “the sacred language.”

Yiddish has a long and colorful history. It is primarily a language of Ash-kenazi Jews, though even segments of this group have often avoided, and at times even snubbed, the language. Nonetheless, Yiddish holds a prominent place in the hearts and minds of millions of Jews the world over.

Yiddish traces its roots to the beginning of the second millennium C.E., when Jewish emigrants from northern France began to settle along the Rhine. These emigrants, who conversed in a combination of Hebrew and Old French, also began to assimilate German dialects. The written language consisted completely of Hebrew characters.

At the beginning of the twelfth century, after the horrific pogroms of the First Crusade, Jews migrated to Austria, Bohemia, and northern Italy, taking their new language, Yiddish, with them. When Jews were invited to enter Poland as traders, Yiddish incorporated Polish, Czech, and Russian language characteristics.

Yiddish served the Jewish people well because it was an adaptable and assimilative language, absorbing some traits of the tongues spoken in the places Jews lived. Consequently, even English words and phrases made their way into Yiddish after the waves of immigration into the United States by European Jewry at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Keep in mind that, just because Yiddish means “Jewish” in Yiddish, that doesn’t mean that these words are synonymous. Jews do not speak “Jewish.” Jewish is an adjective, while Yiddish is a noun that describes a particular Jewish language.

Although Yiddish was the chief vernacular of Ashkenazi Jews, not all Ashkenazi Jews spoke Yiddish. For one thing, it was the vernacular not of scholars but of the ordinary people. The language for prayer and study remained Hebrew, although Yiddish was often used myeshivas (religious schools) to discuss the texts. The fact that Yiddish had to do with the daily tasks of living is reflected in the language itself, and this is one of the factors that makes Yiddish such a unique and alluring language—one that is peculiarly Jewish.

Yiddish is a social language, replete with nicknames, terms of endearment, and more than a good share of expletives. It has its proverbs and proverbial expressions, curses for just about every occasion, and idioms that reflect the fears and superstitions of the times. To learn and know Yiddish is to understand the Jews who created and spoke the language hundreds of years ago.

Yiddish is not the only language to have developed within Jewish communities in the Diaspora. Over the centuries, there have been and remain other languages, dialects, and vernaculars Jews have used to converse amongst themselves. Many Sephardic Jews from Arab countries still speak a mix of Hebrew and Arabic, and Sephardic Jews have their own international language known as Ladino or Judezmo. Ladino is written in either Hebrew or Roman characters and is based upon Hebrew and Spanish. It made its appearance as early as the Middle Ages and it is still spoken in Turkey, North Africa, Palestine (Israel), Brazil, and other parts of South America.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Yiddish was the daily language of an estimated 11 million Jews all over the world. A short time later, this number was reduced by more than half; by the middle of the twentieth century, the language could have been placed on the endangered species list.

Even at its apex in the early twentieth century, Yiddish had its detractors. German Jews, who were very much integrated in the greater German society, were embarrassed at what they considered to be a bastardized version of the sublime German language. In the United States, Sephardic Jews who had lived there for many generations were chagrined at the foreign tongue their “greenhorn” compatriots used. Furthermore, Zionists rejected Yiddish in favor of Hebrew, which they wanted to revive as the vernacular of a new Jewish state.

The most important factor in the rapid decline of Yiddish was the Shoah (Nazi Holocaust), which destroyed entire communities of Yiddish-speaking Jews. When the survivors immigrated to Israel, they discovered that Yiddish was frowned upon as a language of the “ghetto” that reflected a subservient mentality.

However, in recent decades Yiddish has shown itself to be as stubborn and resilient as the Jewish people themselves when it comes to threats of destruction and extinction. In the United States, colleges and universities offer Yiddish courses, and special organizations and groups promote Yiddish both in the United States and in Israel, where there is now a greater acceptance for the language.

Yiddish literature in America

Although it was born as a spoken language, Yiddish eventually made headway in literature produced mainly in Eastern Europe and later in the United States. For instance, you are probably familiar with the musical Fiddler on the Roof, but did you know that it was inspired by the collection of stories titled Tevye’s Daughters, written in Yiddish by Sholom Aleichem?

Unfortunately, while a multitude of rich and immensely attractive Yiddish stories, novels, poems, and essays exist, unlike the stories from Fiddler on the Roof, most Yiddish literature has never been translated.

Yiddish literature can be divided into three periods: the period of preparation, the classical age, and the postclassical period. The first of these is the longest, spanning seven centuries. During this time, most Yiddish literature consisted of devotional works whose purpose was to make Judaism more intelligible to ordinary people. Perhaps the most noteworthy of these writings is the Tz’enah ur’enah, a liberal reworking of the stories from the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses), written by Jacob ben Isaac Ashkenazi.

However, there were also other modes of expressing Yiddish literature during this period. Beginning in the twelfth century, roving Jewish minstrels wandered through Germany reciting Gentile romances in Yiddish. By the fifteenth century, books of poetry, stories, and folktales appeared in Yiddish. In 1686, the first Yiddish newspaper was published in Amsterdam.

In the eighteenth century, Yiddish was the language used by the Hasidim in recounting the numerous tales and stories of the Ba’al Shem Tov and the ensuing masters of the movement. But it would take another hundred years for Yiddish literature to truly come into its own.

The classical age of Yiddish literature was brief in duration but brilliant, bold, and beautiful in its bloom. This period commenced in the late nineteenth century and ended fifty years later. While there were many distinguished writers of Yiddish literature during this time, three stood at the forefront: Sholom Jacob Abramowitz, best known as Mendele Mokher Sefarim (Mendele the Itinerant Bookseller); Sholom Rabinowitz, known as Sholom Aleichem; and Isaac Leib Peretz. These three luminaries of Yiddish fiction wrote about everyday life in the shtetl (small Jewish villages in Eastern Europe) and in the pale of settlement in Russia.

Each made a unique contribution to the body of Yiddish literature. Mendele Mokher Sefarim was the first to employ Yiddish as a vehicle for literary creation. Sholom Aleichem was perhaps unequaled in his ability to depict the authentic human condition of his day with humor, gentleness, and profound sadness. Peretz, trained as a lawyer and the most intellectual and sophisticated of the three, provided a thread of psychological finesse in his work.

Yiddish poetry gained literary merit in the twentieth century. Many Yiddish poets emigrated to the United States and Israel, where their new milieu helped shape their work. For example, Morris Rosenfeld, who lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, wrote poetry protesting the inhumane conditions of the slums and sweatshops. Other notable poets were Simon Samuel Frug, Hayyim Nahman Bialik, and Chaim Grade, whose poetry frequently dealt with the Holocaust.

Yiddish drama began to take hold with the establishment of theaters in Romania, Odessa, Warsaw, and Vilna toward the end of the nineteenth century. However, the Russian government closed numerous Yiddish theaters in the 1930s, sending actors scurrying for safer shores. With many of these thespians settling in the United States, New York soon became the hub for Yiddish theater.

Yiddish newspapers not only provided a way for Yiddish writers to make a living but also offered an outlet for their fiction. A number of Yiddish tabloids published stories and columns for readers who couldn’t always afford books. In 1863, the weekly Kol Mevasser was founded in Odessa, and in 1865, the first Yiddish daily newspaper, Yiddishes Tageblat, began publication in New York City. Perhaps the most renowned of the Yiddish papers was The Jewish Forward, a Yiddish daily founded in 1897. It is still in publication today, although it is now a weekly, published in English with a special Yiddish edition.

Along with a recent resurgence of the Yiddish language, Yiddish literature has become more accessible, particularly with the publication of anthologies. How long this revival will last remains to be seen. Yiddish, unlike Hebrew, is not the holy tongue of Judaism, and is not shared by all Jews. As the demographics of Jewish communities change, there is less incentive for Jews to learn Yiddish, and with each generation less and less people know how to speak it.

Like Jewish literature, Jewish music has played a large part in binding the Jewish people together, particularly during the Diaspora. Jewish music is a mammoth topic that can never be fully summarized in a book such as this one. Suffice it to say, today there is a resurgence of Jewish music called klezmer music, reminiscent of the times when groups of itinerant musicians went from village to village in Eastern Europe, entertaining the local Jewish populace with folk songs and folk dance as well as traditional music. Another branch of Jewish music is comprised of traditional and contemporary songs in Hebrew that originate from Israel.