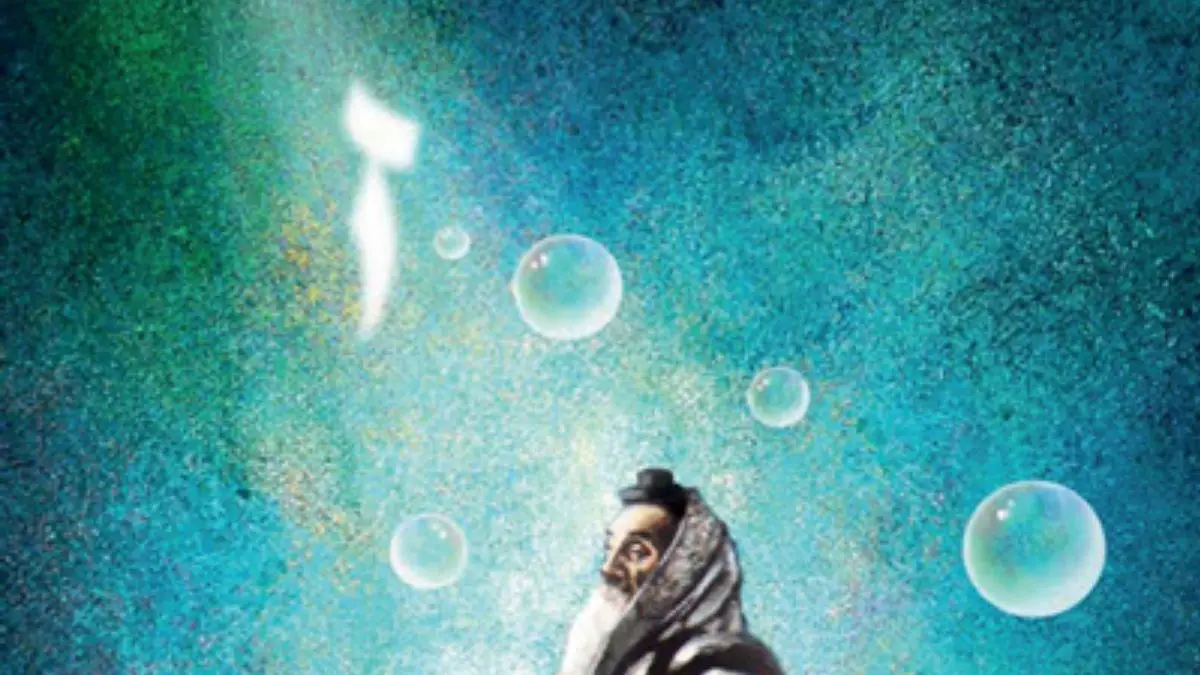

Zayin is the seventh letter of the Hebrew alphabet, and its numerical value is seven. Therefore, the zayin has a strong association with the seventh day, Shabbat, the day of rest.

Remember the Shabbat Day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work; but the seventh day is a Shabbat unto the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any manner of work—you, your son, your daughter, your manservant, your maidservant, your cattle, and your stranger that is within your gates. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea and all that in them is, and rested on the seventh day; wherefore the Lord blessed the Shabbat Day and hallowed it.

According to Jewish tradition, success in the six days of work depends on the blessing bestowed upon us by resting on the Shabbat. Just as the true musician is recognized by his ability to accentuate the intensity of musical pauses, so does the quality of human existence totally depend on our capacity to “pause” and cease all our work on the Shabbat.

The Shabbat is a gift that we are commanded to extend to our animals, to those who work for us, to strangers, and to all who are within our gates. For one day a week all creation is called to experience the bliss of stillness.

We live in a time-based reality, and our bodies are wired to function rhythmically, in intervals such as waking, praying, eating, working, and sleeping.

Shabbat offers us an island in time that is disconnected from the demands and requirements of our everyday existence. Just as God rested from His work, so too do we take a rest from ours. We spare both the universe and ourselves from our manipulations. We do not make changes in the world around us. Instead, we step back and enjoy the world as it is.

The Shabbat is the ultimate expression and exercise of our freedom. Only human beings have been endowed with the blessing of choosing rest. On Shabbat the telephone is ignored, television and radio are silent, and food has already been cooked and only needs to be enjoyed.

There is no traveling, and any thoughts, activities, or speech having to do with money-related subjects, are avoided for almost twenty-six hours.

On the other hand, the Hebrew word “זן”– zan refers to sources of nourishment for humans, and the word “זין” – zayin itself means “weapon,” which hints at the “struggle” of earning a living.

This is only an apparent contradiction. Work can be so all-consuming that, in our effort to earn a living, we can forget to “make a life.” The Shabbat is the cure for the Yang totally taking over the Yin (the introspective aspect of life). The Maharal of Prague explains that the number 6 symbolizes the six directions of space (above, below, and the four lateral directions), in which physical labor takes place, while 7 is the center, the untouchable heart of the cube—the Shabbat, the source of all the blessings for the entire week.

In order to gather the strength to meet the demands made of us during the six workdays, we must reconnect to our higher self by recreating our own center. The effort involved in making this day intensely different from the rest of the week is parallel to the effort of working with an honest, pure, and enlightened state of consciousness on the other six days.

Sefer Yetzirah connects zayin to the month of Sivan, in which the Torah was given on Mount Sinai, and to the tribe of Zebulun. We can wonder whether it might not be more appropriate to associate the Torah revelation with the tribe of Issachar, the tribe of scholars, rather than with the entrepreneurs of Zebulun.

In Jewish thought, however, the way we earn our living is of major importance in our spiritual lives. Doing work that is not ours is like “sleeping with a prostitute.” According to Kabbalah, finding the work that best suits us is as crucial as finding our “soul mate.”

God joins work partners as well as soul mates. Honest and correct partnerships are so important that the sages tell us that the first question a soul is asked when it reaches the Afterlife is: “Were you honest in your business dealings?”

Torah Yin Yang

The correct energy dynamics between the Yang and the Yin aspect of zayin is central to Judaism. The Torah does not advise spiritual seekers to go to a convent or a monastery to meditate. Rather, the Torah clearly encourages one to “work for six days, and rest (a deep complete rest) on the seventh day.” On Shabbat, our commitment is in the realm of “not doing.” During the week, the effort is about “doing” in a state of higher awareness. In TCM terminology, we could call the Shabbat the Yin that nourishes the Yang.

Keeping Shabbat is central to Judaism. Thus, we understand that the sanctification of God’s name occurs in the dimension of stillness and meditation. Says the prophet Ezekiel: “Not in the wind, not in the storm…but in the still small voice…” We read in the liturgy of the Shabbat afternoon, “a rest of peace, serenity, a perfect and complete rest, which You want us to experience. May Your children recognize and know that from You is their rest, and by their rest they sanctify Your Name.”

The need to stop creative activity and go inside during Shabbat can also be explained from an astrological perspective. The Hebrew name of the planet Saturn (Shabtai) shares the same root as the word Shabbat. The energies of this planet, which rules the seventh day, are not conducive to action.

Saturn is known as the planet that blocks and thwarts creative human effort. It is therefore much more natural to withdraw and abstain from action and work on this day. For centuries the first Christians also observed the seventh day on Shabbat, Saturday, the day of Saturn, and not on Sun-day. From the astrological perspective, the energy of the sun is much less conducive to introspection and withdrawal and more inspiring to ‘action’. Maybe one of the reasons why Western society is so extroverted and unable to go ‘inside’ is that its day of rest is under the influence of the Sun, a heavenly body that is inspiring the fire of activity. In fact, many Westerners spend their day of “rest” engaging in active sports, traveling on crowded highways, or participating in social activities that deprive them of the rest available on the seventh day.

As mentioned above, the letter zayin is associated with the tribe of Zebulun.

In reference to the continuous journeys of this tribe of navigators and traders, it is written: “Rejoice, Zebulun, in your going out.”

External movement, the capacity to go far, is possible especially thanks to the ability to return “home.” The root of the name Zebulun (from זבול – zevul, “abode”, “dwelling”) means to “have a home,” a deep root to return to.

According to Maimonides, staying healthy, happy, and balanced when working, traveling, extending oneself beyond our limits, depends on being able to live in a correct rhythm of strain and rest. Therefore, if we do not keep Shabbat, we may end up consuming our Yin. Yin is the inherited essence of our life force needed to keep our immune system healthy. Instead of depleting our Yin through overworking, it is better that we should keep it for staying alive!

Our society does not accord to the night, the Queen of the Yin, the respect we owe her. Thanks to electricity, we can deny the fact that it is night, the time for sleep and energy recuperation. We can pretend that it is still day!

As Nechama Sarah Burgeman points out in The Twelve Dimensions of Israel, Zebulun’s stone, as it appears on the High priest’s breastplate, is a white pearl. Our sages explain that its white color alludes to the whiteness of silver, which symbolizes wealth. Because Zebulun understood the pure source of money—that everything belongs to and comes from God—he was able to rectify the greed (symbolized by the color green) usually associated with money. Perhaps this is another reason that Zebulun merits being associated with the month in which the Revelation at Mount Sinai occurred. This cosmic event impressed on all of our souls that Ain od milvado (“There is nothing besides God”). All of the detailed Divine laws guiding our conduct in the material world of plurality return our consciousness to this truth.

Zayin means a “metal sword.” The metal sword cuts away the old in order to make space for the new (also “new air,” as we mentioned in the chapter on the letter alef: new ideas, new relationships, etc.).

Metal is also associated with the management of money (metal coins), which is an important issue for traders and for old age, represented by metal. Also, metal and the lungs have to do with the going in and out of breath (as we saw in the chapter about alef) as well as the soul going into and out of our body; birth and death. The quoted verse, “Rejoice in your going out…” can be associated with the idea of the metal element and old age as a time of spiritual preparation for leaving this world, letting go in joy, celebrating the last stages of detachment from human evolution, of separating from our possessions, money, and people.

Realizing the bliss of the World-to-Come can help some people to breathe their last breath in peace and awareness of the infinite Divine love. This is why not only Buddhism and Kabbalah, but also psychologists and doctors today are trying to teach terminally ill people to be ready to face the world to come with a smile. “Rejoice, Zebulun, in your going out…” This attitude is not easy in a society that mostly lives as if there is only “one world”. Deep spiritual preparation is needed in order to not be afraid of the unknown and to establish a connection of love and trust to our spiritual guides, beloved parents, and grandparents who are already living in the World of Heavens.

Zayin is also the first letter of the words זמן – zeman (“time”) and זכר – zecher (“memory”). Much of our successful spiritual and psychological growth depends on our relationship with time and memory.

The Name of God, the Tetragrammaton, suggests the union of past, present, and future: by combining the letters of the Tetragrammaton in various ways, we obtain the Hebrew words for was, is, and will be. This hints to how God is beyond all time, yet involved in every aspect of all time dimensions that we pass through.

Observing the Jewish holidays helps create a well-balanced relationship with these three dimensions of time. On the one hand, as we reconnect to the events of the past through rituals and prayer, we experience the trials and salvations that our forefathers experienced. In doing so, we also reactivate the same energy and states of consciousness they experienced, which helps reinforce our faith in the positive promise of our future.

The holiday of Passover illustrates the importance of remembering: we recall the story of the Exodus to remind ourselves of our past slavery, in order to remain constantly aware of the danger of spiritual, emotional, and psychological decline into all kinds of slavery (food, drugs, work, emotional traumas, relationships…) On Passover, eating maror (bitter herbs), dipping in salt water (to feel the taste of tears), and the numerous rituals of the Pesach seder have one single aim: to recall and arouse our awareness of the bitterness and suffering of slavery—of any kind of slavery—and the possibility of freedom.

By remembering God’s continuing presence in our personal history, we also can access the different qualities of time, related to the different “faces” of Divinity. As is written in Ecclesiastes:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to reap that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to reap, and a time to sow; a time to keep silent, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

Flowing with time is a religious precept in Judaism. Our sages teach that Pesach (“Passover”) is a time when all of nature is escaping from the chains of cold and winter. Similarly, Yom Kippur, the Day of Forgiveness, could only be in the month of empathy and compassion, and the day of Purim (in which we must reach the state of equanimity necessary for not seeing the difference between good and bad in our lives) could only happen in the full moon of Adar, the month of Pisces.

In our daily life, if we speak when we should listen, if we remain silent when we should speak up, if we embrace when we should refrain from embracing, if we want to win when we have already lost, we are not tuned in to “God’s time.”

For thousands of years in the East, the Book of Changes has been a guide for men of wisdom to inquire and tune in with the right times for action and contemplation, following the Divine energy flow.

A tool for tuning into the present moment is the practice of reciting the blessings that are appropriate for any particular given situation. For example, when someone dies we recite a particular blessing of accepting the Heavenly decree.

There are special blessings we recite when we see the ocean, smell the scent of a fruit, or eat a certain type of food. Blessings are a type of meditation through which we totally immerse ourselves in the present moment. Thus, we avoid the psychological malady of either constantly projecting into the future or digressing into the past.

The condition of absolute awareness can be learned from children, who know how to totally concentrate on what they are doing at any given moment. As Zen masters also teach: “When you sit, sit; when you walk, walk; when you eat, eat!”